“I am always doing that which I cannot do, in order that I may learn how to do it.”

― Pablo Picasso

Learning to do something requires us to step beyond our comfort zone. Just as hearing someone describe a watermelon to you will not allow you to taste it, reading about improvisation does not allow you to become an improviser. At some point, it is essential to sit down at the keyboard and, as Nike encourages us, “Just do it.”

How to Learn

Some people learn best by watching someone else do the task first. Others need to hear someone give an example. This is one of the reasons why I include YouTube videos at organimprovisation.com. While all of the videos provide auditory examples, when I am searching for videos to include, I will give a preference for those where you can see the player’s hands at the keyboard as well. I know from my own personal experience that it has been very helpful in my learning process to be able to see exactly how someone is creating the sounds that I am hearing. The organ offers so many different sound combinations and such complex sounds (through the use of mixtures and other upper work), that a quick glance to see where the hands are at the keyboard can settle many questions that the ear might have posed. I remember even my teacher peering around the corner once after I had been asked to improvise with my left hand and feet alone. I’m sure he was checking to make sure I didn’t slip my right hand into the texture!

Some people also learn best by touch. You can explain to them and show them, but until they can use their hands and do it for themselves, their learning will be incomplete. For me, this is where scales, arpeggios, cadences and other progression exercises help train us as improvisers. Any one who has ever memorized a piece of music is familiar with the idea of muscle memory. We need to find ways to train and take advantage of this muscle memory when we improvise as well. Knowing our muscles know where to go next frees up brain power for us to focus on form or any of the other elements we need to consider as improvisers.

Modes

As a young piano student, I learned to play all the major and minor scales, along with arpeggios, chords and cadences. These drills helped build technique and were my introduction to harmonic theory. If you have not learned to play scales, arpeggios, chords and cadences (I-IV-I-V-I) in all the keys, I strongly urge you to do so. While I have most often done these at the piano, we shouldn’t forget to practice them with our feet as well. Go as slowly as you need to in order to play accurately, then you can work for speed.

While the major and minor scales are part of most every musician’s formation, other modes are frequently omitted or only touched briefly. As an improviser, I believe the more tools we have in our toolbox, the better we will be prepared to improvise on any given theme. For this reason, I’d like to recommend spending some time getting to know other modes as well as we know the major and minor modes.

Dorian Mode

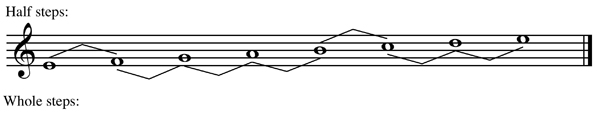

As mode number one in the codification of the church modes used for Gregorian chant, I’d like to start with the Dorian Mode. It differs from the natural minor scale by having a raised sixth degree.

Rather than playing minor scales this week when you practice, how about playing the Dorian mode? Be sure you can play the mode starting from each of the different pitches. If you need to verify or want to have a reminder in front of you, I prepared a pdf that you can download here.

Aside from scales, here are a few other ways to practice and learn the Dorian mode:

- Play the same arpeggios, chords and cadences that you would play when practicing a major or minor scale.

- Practice any other technical exercises that you might normally do (Czerny

or Hanon

or Hanon for example) in the Dorian mode.

for example) in the Dorian mode.

- Change the key signature for a hymn to the equivalent Dorian mode signature. This will be easiest with hymns that have no accidentals, but you could also try with more complicated hymns.

- Create melodies in the Dorian mode. Be sure to include the scale degrees that make it different from the natural minor so that you can learn to hear the difference.

- Practice the Dorian mode in different keys by playing a pedal point on the tonic and chords or melodies with the hands. After 1-2 minutes, change the pedal point and tonic to a new key.

What else can we do to get the Dorian mode into our ears and fingers?

In the coming weeks, I plan to include posts about other modes on the website, explaining how they are constructed and identifying themes that are in the mode. All of the suggestions for the Dorian mode today can be (and should be) applied for each of the other modes that will be presented in the weeks to come. Part of creating colorful improvisations is the ability to use different modes. Regardless of how you might choose to go about learning the modes, be sure to find a way to include them in your improviser’s toolbox.

Hoping you will venture into new territory in order to learn more,

Glenn

Recent additions to organimprovisation.com:

Mode:

Newsletter Issue 18 – 2014 09 01

See the complete list of past newsletter issues here.

Sign up to receive future issues using the box to the right on this page.

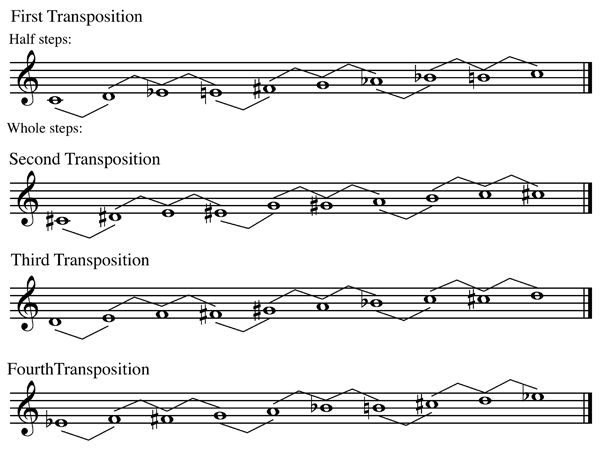

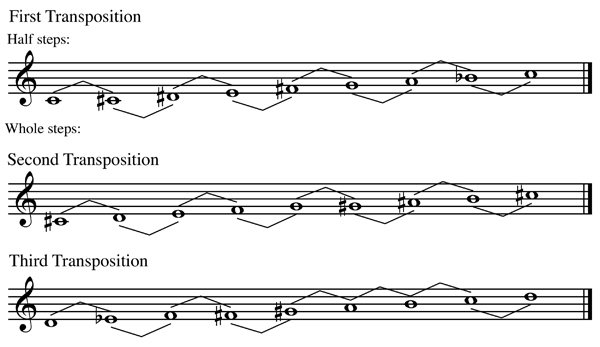

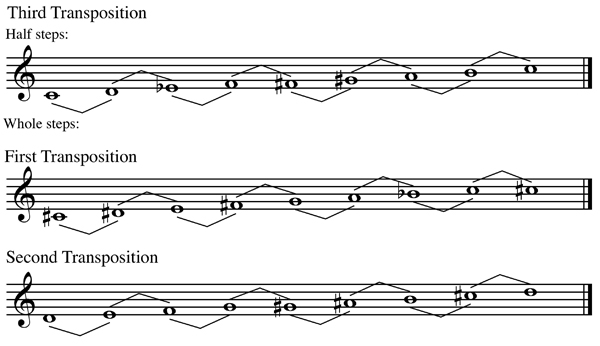

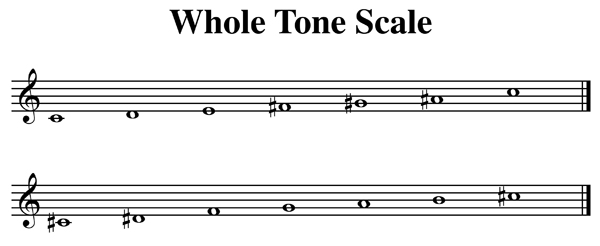

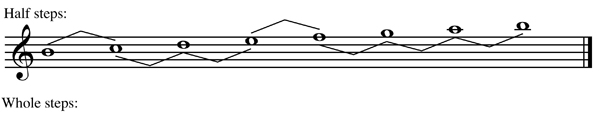

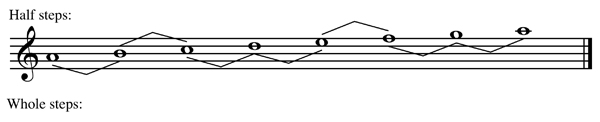

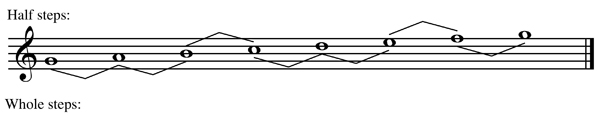

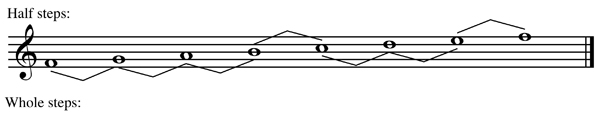

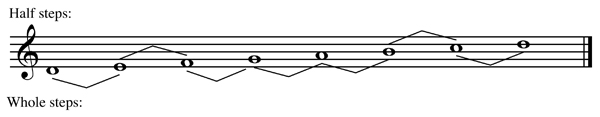

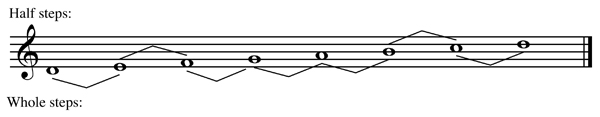

, Olivier Messiaen identifies seven modes of limited transposition. Within the chromatic system of twelve sounds, Messiaen has identified groups of pitches which after a certain number of transpositions are no longer transposable. These modes may be used both melodically and harmonically and give the impression of several tonalities without polytonality. The first of these modes is the whole tone scale. The second mode is probably the best known of the modes Messiaen identifies as it is also known as the octatonic scale.