One of the most magical musical experiences I ever had occurred when I was improvising a passacaglia once during communion at the Cathedral in Aix-en-Provence. Starting from a single soft pedal line, I steadily built a crescendo of sound and activity until I reached full organ before finally concluding softly. I remember feeling like I was having some sort of out of body experience as I turned to look over the railing to see how much longer I would need to play. I knew something special had happened at that moment because I was literally shaking at the end of the piece, and the priest thanked me for sharing such wonderful music when he made announcements. Perhaps the scariest part was that I knew I had to start playing again in just a moment for the Sortie!

Focus

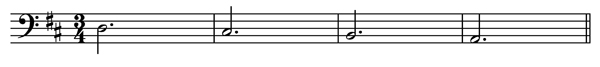

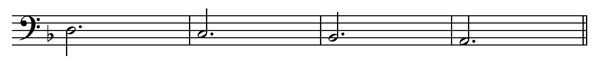

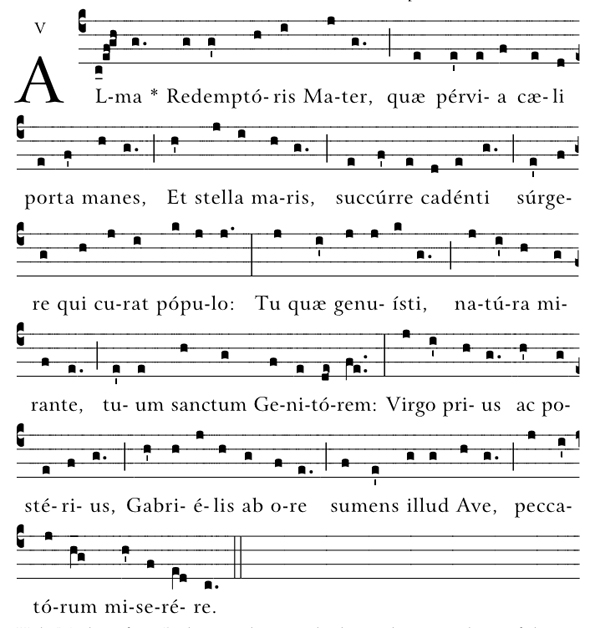

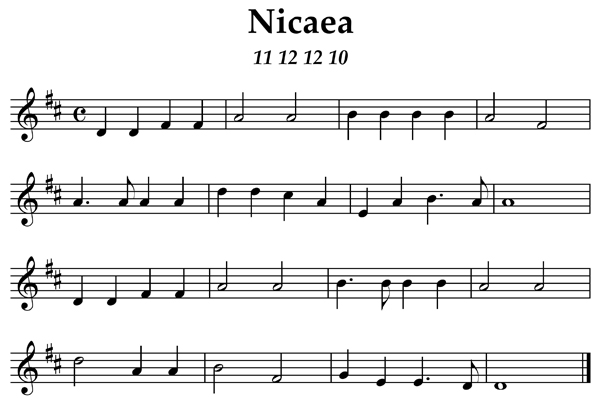

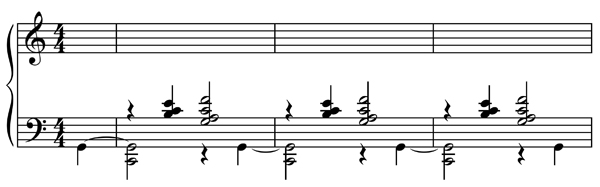

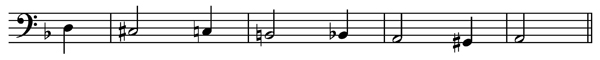

While I have searched for years to return to that same mental state where the music just flowed out of me, I recently heard an interview with Steven Kotler (author of The Rise of Superman: Decoding the Science of Ultimate Human Performance) where he identified some of the characteristics that help create this state which researchers now call “flow.” The first of the seventeen triggers that he identifies is focus. I believe as an improviser, one of the best ways to focus is to improvise over a ground bass or passacaglia. On that day in Aix, I had a bass line written out with figures above the notes to remind me of my intended harmonies. An easy place to start would be a short descending scale in major:

Goals

The second trigger Steven Kotler identifies is to have clear goals, i.e. to know what we are doing and why. A passacaglia, not only gives us focus, it provides a clear definition of what we are to play. At Aix, I also had a reason to play that passacaglia: to provide music during the distribution of communion which would last 6-8 minutes. That was my larger goal, My shorter goal was each variation of the bass, and the immediate goal was what to play for the next chord.

Feedback

The third trigger for flow is feedback. As an improviser, we receive immediate feedback on our results. This is not a test or other written assignment where we choose an answer or what to say and find out sometime later (if ever) whether we were correct or pleased the reader. Hopefully, our ear will let us know instantly if the notes we have chosen to play have met our goal or not. The other advantage of a passacaglia is the harmonic and rhythmic drive forward of the form. We use the feedback to move us forward, continuing with an idea that works, making changes to ideas that were not so successful.

Bored or anxious?

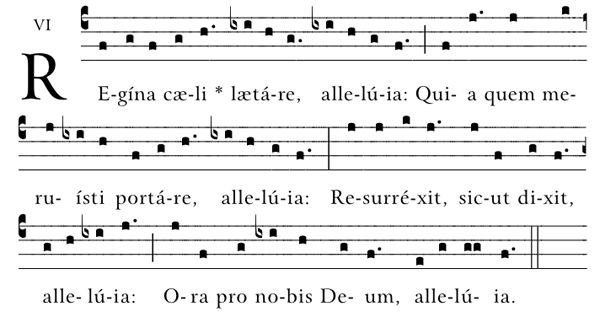

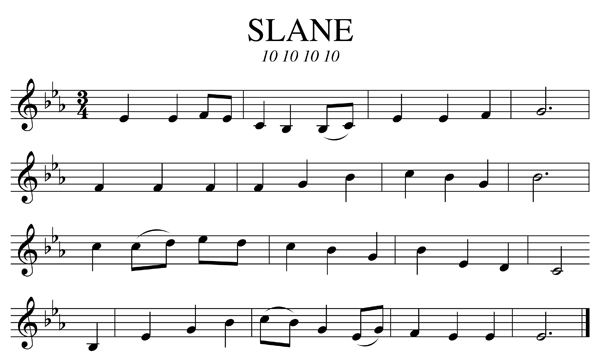

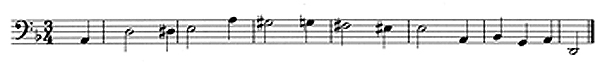

The final psychological trigger identified by Steven Kotler is the degree of difficulty of the task. If we are bored or otherwise unchallenged, we are not likely to get into flow. If the task is too daunting, we will most likely be nervous, and doubt will keep us from achieving our best performance. Flow lies somewhere in the middle where we have confidence in our skills and yet feel challenged by the task at hand. Perhaps the themes above are too simple for you. How about one of these more chromatic basses?

Regardless of the complexity of the theme, we can still challenge ourselves by increasing the harmonic complexity, increasing the tempo, increasing the rhythmic complexity, or setting other technical challenges for ourselves.

The Zone

Perhaps it’s simply because of that experience I had in Aix, but I have a special interest in passacaglias. I believe I’ve discovered part of the reason now through Steven Kotler’s seventeen triggers for flow. What forms do you improvise well? Are there any styles or processes that you use to create your best music? While I might not have told you how to improvise a passacaglia today, I hope I have given you some inspiration and reasons to do so. Hopefully this grounded form will keep you focused so that you too can enjoy that same out of this world experience that I had in Aix.

May all your improvisations be fabulous!

Glenn

Recent additions to organimprovisation.com:

Organists:

Review:

Themes

Newsletter Issue 16 – 2014 08 18

See the complete list of past newsletter issues here.

Sign up to receive future issues using the box to the right on this page.