For the last couple of weeks, we’ve been working from Charles Ives’ Variations on ‘America’ to discover improvisation ideas and practice techniques. After looking at the fireworks of the first variation, the polonaise, and the introduction, today we turn to the chromaticism of Ives’ second variation.

Chromaticism

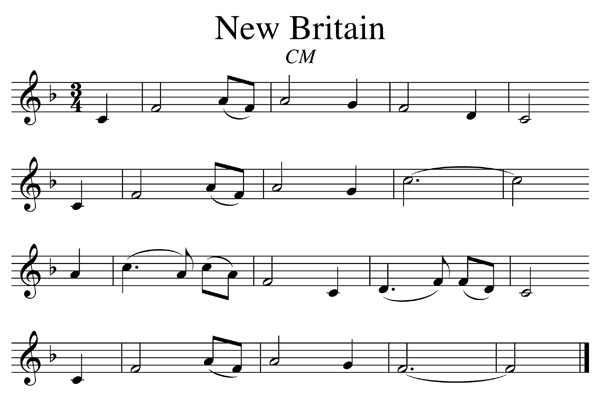

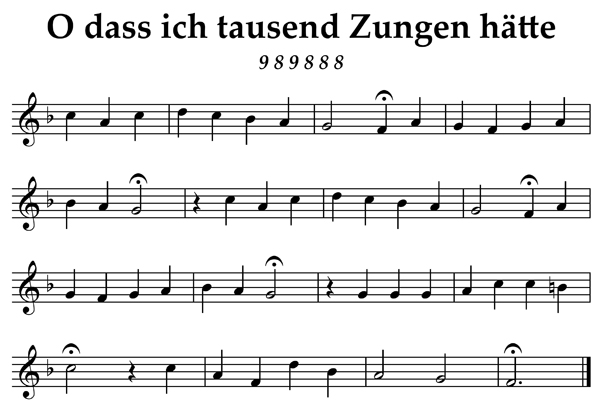

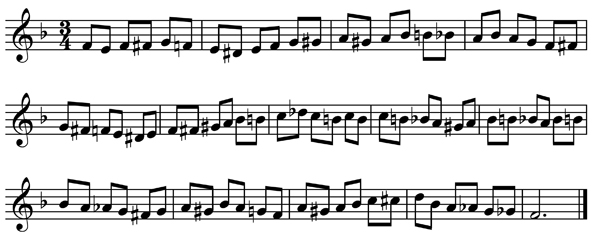

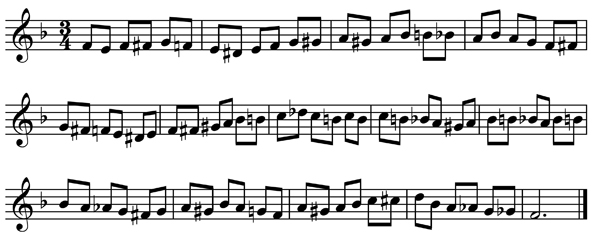

The first difference to notice with this variation is that Ives has changed range. The melody begins one octave higher, allowing him to use chords with more open voicing – and thus more space for chromatic fill! This variation is filled with stepwise motion (whether chromatic or diatonic) in the lower voices. Only the soprano melody remains largely untouched. Ives also moves from the predominantly quarter note rhythm of the theme to consistent eighth note activity. As our first exercise (since Ives didn’t touch the soprano), let’s try to tun the melody into a flurry of chromatic eight notes:

Add chromatic passing tones between steps in the melody and chromatic neighbor notes for repeated notes. It may be overkill to do this only to one voice, but I think it is a great practice technique to explore, working our way through each of the voices in the standard harmonization one after the other. Do the same exercise with the alto, tenor, and then the bass alone. For step two, play the full harmonization while adding chromatic neighbor and passing tones to one voice. After you are comfortable focusing on one voice at a time, your ear will likely have led you to discover spots where chromaticism works better in one voice than another. Play through the harmonization again now adding the chromaticism in the voice where it works best.

Some tips to consider as you explore: In four-part texture, one of the notes of the chord is doubled. This is probably not the note to alter chromatically unless it is the root of the chord and you are adding the seventh. (Ives ignores this in m.4 of this variation, but ends up with parallel octaves between the soprano and this inner voice.) Thirds of chords can easily be major or minor. Choose whether to move from major to minor or minor to major based upon where the voice needs to go next. Fifths of major chords can be raised; fifths of minor chords can be lowered. The diminished triad (and fully diminished seventh chord) can transport us easily from one key to another, so provide excellent transition material (see m.6 of variation II). Ives also reduces his texture to only three voices at times in order to highlight the chromatic lines (and lessen his concerns about doubling). As you become comfortable shifting from one voice to another, be sure and try combining chromaticism in multiple voices at the same time!

And now, faster!

Typically when creating variations, the rhythms move from quarters to eighths, through triplets and on to sixteenth notes. After exploring eight notes, the third variation on ‘America’ by Ives suggests the triplet feel by shifting to 6/8 time. Ives also sets up an accented chromatic neighbor note in the accompaniment as a motif for this variation. Leaving modulation and discussion of the interlude for next week, Ives also changes keys here. Rather than change so many items at once in our practice, how about doing them one at a time? Stick to the original key, but instead of chromatic eight notes, add chromatic triplets! Rather than using passing and neighbor tones on the weak beats, try to use more accented chromatic neighbors. It would be overkill, but what if each note of the soprano (or alto or tenor) began a half-step lower and slid into the proper pitch? (How many vocalists have you heard scoop into a note? Why can’t we try it at the organ!) After you are comfortable in the home key, choose another key in which to practice the harmonization and addition of chromatics. Start again with eight notes and progress through the same steps outlined above.

After triplets, move on up to sixteenth notes. The final variation Ives provides keeps the same chromatic neighbor from variation three in the accompaniment, returns to the tonic key, but increases excitement by using a constant sixteenth note motion passed between the voices (including some challenging runs for the feet). While it looks complicated on the page, it really grows out of the techniques covered in the earlier variations.

While the road may offer many choices for the twists and turns to take, I hope you will take each step forward, confidently making progress towards creating your own fireworks at the organ!

Glenn

Recent additions to organimprovisation.com:

Review and Competition:

Newsletter Issue 13 – 2014 07 21

See the complete list of past newsletter issues here.

Sign up to receive future issues using the box to the right on this page.

Website:

Website: