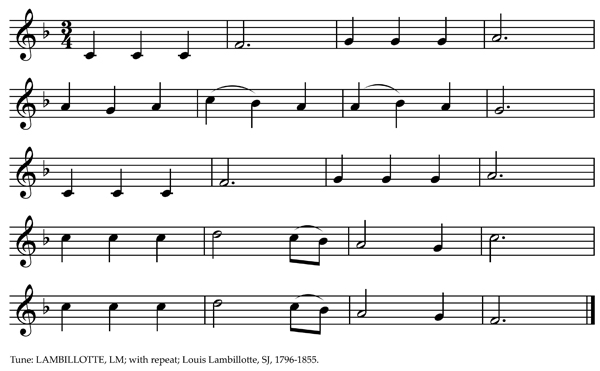

Generally known with the lyrics “Come, Holy Ghost,” the tune Lambillotte was written by Belgian Jesuit Louis Lambillotte. I prepared a non-standard harmonization of the tune available as a PDF download.

Summer Improv Courses 2016

The Summer is a popular time for conferences and special courses. Here’s a list of opportunities to study improvisation at the organ this summer. If you know of others, please email me or share them in the comments so that I can add them to the website.

- London Organ Improvisation Course – July 18-21 in London, England. The guest tutor will be Otto Krämer

- Classical Music On The Spot – June 27-July 3 at Eastman School of Music in Rochester, New York covers 18th-century repertoire and improvisation skills. Knowledge of figured bass is required.

- Jehan Alain Society: 48th Organ and Improvisation Course – July 18–23 in Romainmôtier, Switzerland. Emmanuel Le Divellec and Tobias Willi teach improvisation to a maximum of 14 students. The complete two week course also includes instruction by Michel Bouvard, Bernhard Haas, Guy Bovet, and Michel Jordan

- Organ Academy in Saessolsheim (Alsace, France) – July 21-27 In addition to repertoire, Freddy Eichelberger and Francis Jacob will also wok on improvisation.

- Haarlem Summer Academy – July 18-22 Thierry Escaich teaches advanced improvisation; July 25-30 Peter Planyavsky teaches advanced improvisation and Jos van der Kooy teaches improvisation for beginners.

- 12th International Summer Academy of Music – July 22 – August 5 offers organ instruction with Jürgen Essl and Jean-Pierre Leguay on both repertoire and improvisation. Participation is limited to 12 organists. The course takes place in the Landesmusikakademie Baden-Württemberg in Ochsenhausen, Germany.

- Smarano International Organ Academy – July 25 – August 6, includes improvisation instruction by William Porter and Edoardo Bellotti

- Organ Academy South Germany – Upper Swabia 2016 – July 28-31 on the 1780 Holzhey Organ in Obermarchtal Monastery. Johannes Mayr offers instruction in repertoire and improvisation.

This summer is also the National Convention of the American Guild of Organists. It will take place in Houston July 19-23. Typically there is an improvisation competition and several workshop presentations on improvisation during the convention. I only spotted one improvisation workshop: Adagio Lost and Adagio Regained: A Study of the Lost Art of Improvising in the Adagio Genre, with Emphasis on Handel’s Organ Concertos presented by HyeHyun Sung. The NCOI competition was restructured for this year with the preliminary round taking place last summer. (See my critique here.) No information about the competition is currently on the Houston website…

I am still considering offering a couple of days of improvisation instruction here. If you would be interested in coming to study with me at the Cathedral July 28-30, 2016, please let me know. Space for active participants will be limited. If there is sufficient interest, I’ll share more details soon.

Hoping you take some time this summer to improvise better,

Glenn

Newsletter Issue 58 – 2016 04 21

See the complete list of past newsletter issues here.

Sign up to receive future issues using the box to the right on this page.

Introducing Dissonance

Our modern ears have become so accustomed to advanced tonal languages that dissonance has become a relative concept. Just a few short centuries ago, composers would not include a third in the final chord of a piece because it was considered dissonant. In the 20th-century, Olivier Messiaen crafted pieces that end peacefully on a dominant seventh chord (as in Le banquet celeste). Context allows us to walk away from this final chord without demanding a traditional harmonic resolution.

Wrong notes

I don’t necessarily remember where I got the idea, but one of the foundational ideas of the instruction I received in improvisation was that there are no wrong notes when improvising. Why then do some notes sound wrong? Why do the pieces I end on a dominant seventh chord usually sound unfinished (unlike Messiaen)?

I believe the simple answer is that these wrong notes make a change in the level of dissonance.

This works both ways. If you are playing in an early tonal language and your melody lands on the minor third while the accompaniment has a major third (F natural above a D-major triad for example), it will certainly sound like a wrong note and a mistake. Likewise, if you are playing in an advanced language with lots of seconds, sevenths and clusters, the appearance of a major triad can sound quite jarring. The sounds are perfectly acceptable by themselves. It is the context that makes them seem wrong.

New Rules

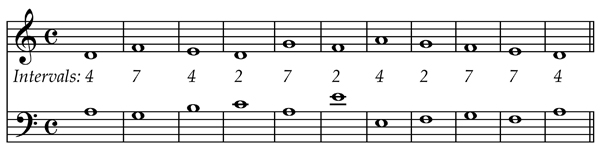

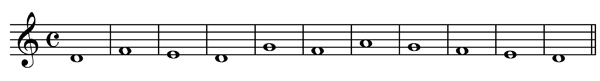

The study of counterpoint introduces dissonance in a very systematic and controlled way. First species allows no dissonance. In the language of Palestrina, this limits us to thirds, fifths and sixths using notes within the mode. If we wish to develop a more modern sound, what if we did first species using only seconds, fourths, and sevenths? For example:

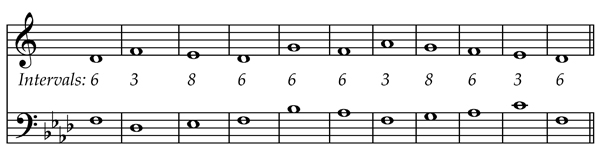

Another alternative might be to keep the intervals restricted to thirds and sixths, but move one hand into another key:

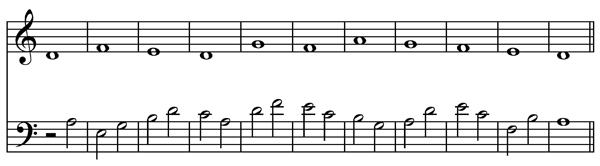

Second species counterpoint where there are two notes against each note of the cantus firmus allows more options for introducing dissonance. Like first species, it can be done without any dissonance (only seconds, fourths and sevenths here):

Or passing and neighbor notes can be included:

With its carefully graded level of difficulty, the traditional path to the study of counterpoint introduces dissonance in a careful and controlled manner. Even if we wish to use a more modern language, we can still apply those same concepts for the introduction of dissonance. Choose which intervals will be consonant for your exercise. As you move into the second and third species, introduce categories of dissonant notes one by one: passing tones, neighbor notes, chromatic passing and neighbor notes, appoggiaturas, and accented passing tones. How do these categories change or alter your dissonance level?

In my first days as a student, I spent an entire year (or two) on two voice counterpoint working slowly through the levels of dissonance and species. Mastery of counterpoint takes time, but that doesn’t mean it has to be dull and boring. Change the rules and keep exploring!

Happy counterpointing!

Glenn

Newsletter Issue 57 – 2016 04 11

See the complete list of past newsletter issues here.

Sign up to receive future issues using the box to the right on this page.

A season of resurrection

Happy Easter! I hope all of you who had extra and important services over the last weeks are now recovered and ready to continue with your improvisation study. During this season with liturgical churches focus on the resurrection of Jesus Christ, it seemed fitting that I should resurrect the newsletter and take up the task once again of encouraging people to improvise at the organ. The message of Christianity has not spread far and wide because it was only practiced by a few people, but because those who practiced it told others about it. We must do the same for improvisation. If you have colleagues that do not improvise, teach them something simple as a way to get started (or send them to explore the previous newsletters).

Happy Easter! I hope all of you who had extra and important services over the last weeks are now recovered and ready to continue with your improvisation study. During this season with liturgical churches focus on the resurrection of Jesus Christ, it seemed fitting that I should resurrect the newsletter and take up the task once again of encouraging people to improvise at the organ. The message of Christianity has not spread far and wide because it was only practiced by a few people, but because those who practiced it told others about it. We must do the same for improvisation. If you have colleagues that do not improvise, teach them something simple as a way to get started (or send them to explore the previous newsletters).

Gradus Ad Parnassum

Aloysius– But are you not aware that this study is like an immense ocean, not to be exhausted even in the lifetime of a Nestor? You are indeed taking on a heavy task, a burden greater than Aetna.

My area of focus for 2016 is counterpoint. I was fortunate as an undergraduate student that my composition teacher included counterpoint exercises as part of every lesson. Most undergraduate theory programs include some study of harmony and counterpoint, but usually spend more time analyzing them than actually creating them. For me, this is the equivalent of learning to read, but never learning to write or speak. As improvisers, we need to learn to speak music, and thus have embarked upon the lifetime of learning Johann Joseph Fux mentions in the quote above.

Gradus Ad Parnassum is one of the classic texts for the study of counterpoint. Written in 1725 by Johann Joseph Fux, it was held in high esteem and used by such composers as Mozart, Haydn, Beethoven, Brahms, and even Strauss. It is written as a dialogue between a student, Josephus, and the teacher, Aloysius, identified in the Foreward as Palestrina. The dialogue is a fictional creation of Fux therefore, but is meant to present the rules of counterpoint (indeed all musical composition) as practiced by Palestrina.

Species Counterpoint

One of the advantages of learning composition through the study of counterpoint is the very easily identified and graded levels. Beginning with only two voices, the student progresses through five species before adding another voice:

- First Species – note against note

- Second Species – two notes against one

- Third Species – four notes against one

- Fourth Species – syncopation

- Fifth Species – florid counterpoint

When creating counterpoint, one of the voices is identified as the cantus firmus. This is the given melody for the exercise that may not be changed. The other voice(s) must be written to follow the rules and fit correctly with the cantus firmus. Here is the first theme Fux provides:

All notes in first species counterpoint must be consonant intervals: 3rds, 5ths, 6ths, or octaves. There are many more rules regulating the movement between the voices, but before we get there, let’s consider some practice ideas we can take away from what we’ve covered so far.

- All rhythms are equal in first species. What happens to a melody or theme if we strip the rhythm away from it? Some hymns are almost all quarter notes, so won’t change much. Others have a variety of rhythms and will sound quite different when equalized.

- Counterpoint can appear either above or below the cantus firmus. Here is a chance to practice our dexterity at the organ. Each of your hands, as well as your feet could be the cantus firmus, while one of the others plays the counterpoint. For an added challenge, play the theme in the bass register with the right hand while your feet play an added melody above on a 4′ (or 2′) stop!

- Fux (and Palestrina) make use of the church modes: Dorian, Phrygian, Lydian, and Mixolydian. If these modes are not part of your improvisational vocabulary, spend some time becoming more familiar with them. Ideas for practicing them can be found here and here. Counterpoint is not required in order to learn a mode.

- Themes are written in whole notes. Practice slowly. Whether it is counterpoint, or some other improvisation technique, take your time. Especially as we move into more complicated counterpoint, never play faster than you can think.

Spread the Word

Improvisation is not an easy task to master. It takes time and practice, but there are ways to start and make it accessible to everyone. In this Easter season when Jesus sent his disciples out to spread the Good News, I hope you will practice your improvisations and share with others the joy and delight you find in creating music in the moment.

Wishing you all the best,

Glenn

Newsletter Issue 56 – 2016 04 04

See the complete list of past newsletter issues here.

Sign up to receive future issues using the box to the right on this page.

Using my iPhone to play the organ

In January, just as I sent out the last newsletter issue, I left to attend the Conference of Roman Catholic Cathedral Musicians in Hartford, CT. A collegial gathering of usually around 60 music directors and organists from across the country, I had not been able to attend for several years, so was really looking forward to catching up with the group this year.

Technology

Pipe organs have been around for many centuries. Technology has led to advances in the ways sound is created and the way it is controlled. While trying to avoid the pipe versus digital debate, the fact that this debate exists I believe has left pipe organs woefully behind in the technological advances of how we can control a pipe organ.

MIDI has been around for over thirty years and is perhaps the only piece of recent technology that might be included on a pipe organ. I suspect many organists that have MIDI never use the capacity because it is primarily seen as a way to add in other sounds to the organ. The organ at the Cathedral has MIDI ports, so when one of my cathedral colleagues told me that I could get a MIDI-to-lightning cable and connect my iPhone to the organ, I became very interested in what I might be able to do.

The Cable

The Cable

I ordered the cable once I came home from the conference and anxiously waited for its arrival. With a recorder app on my phone (MIDI Tool Box), my first thought was that I could now record my improvisations and then take the files to the computer and transcribe them! Some people have spent hours upon hours listening to Pierre Cochereau‘s improvisations to transcribe them. Now with my iPhone, I would be able to have at least a rough transcription with a few mouse clicks!

The Trial and Demo

In addition to capturing the notes I played, the recorder app would also capture the registration and swell pedal movements! Even when studying repertoire, I was encouraged to record myself so that I could coach my own performances. Imagine being able to hear your improvisation again simply as a listener. That fabulous harmonic progression you stumbled into by mistake can now be transcribed, studied, and repeated! Check out the video below for a demonstration of how it works.

Beyond its usefulness for studying improvisation, this set up enables me to transfer pistons between consoles and opens some new possibilities for accompanying.

Conclusions

Pipe organs rely on very reliable technology from centuries past in order to produce sounds, but we don’t have to miss out on other technologies from the 21st century. (Bluetooth even opens the door to wireless connections!) MIDI is a great way to capture improvisations, and I encourage you to take advantage of it if you have it on the organ you play regularly.

Happy improvising,

Glenn

Newsletter Issue 55 – 2016 03 09

See the complete list of past newsletter issues here.

Sign up to receive future issues using the box to the right on this page.

Two Keys at One Time?

One of my tasks during my undergraduate studies was to memorize the C major Prelude from Bach’s Well-tempered Klavier (Book 1). My theory teacher for harmony, Dr. Stefan Young, wanted us to play the piece in block chords and sing the bass line with the harmonic analysis as our lyrics. When I had Dr. Young for counterpoint the next semester and he again assigned the same piece, I was given the additional complicating task of playing the piece not just in any key, but in any two keys at the same time. Dr. Young wanted me to play the right hand in one key while playing the left hand in another. It’s a real mind-bending experiment to try, even if it doesn’t always sound so great…

When I pulled out the hymnal yesterday to practice, I stumbled upon “There Is a Balm in Gilead.” The melody basically is a G major chord, so I thought what if I harmonize it in F major instead. There are a few other key shifts here, but the harmonic rhythm remains slow so that you have time to consider the unexpected colors.

Counterpoint and Fugue

Usually as the New Year begins, may people set goals that they would like to achieve in the upcoming months. Unfortunately, after a couple of weeks, these usually fall by the wayside and go unfinished. How often have you set the same goals on New Years that you set for the last year?

A Word Instead of a Goal

The new trend is to choose a word for the year rather than set specific goals. I like this in that it can be more flexible and can help keep you focused without making you feel guilty about missing a deadline or not keeping up with a routine. One of the reasons goals often go by the wayside is the need to restart after we miss a workout, eat too much, or otherwise miss a step on our plan. Once we miss a step on our goal journey, it is often easier to quit than to figure out what to do next.

As improvisers, we should be well acquainted with missteps and the need for recovery after mistakes. We have to keep going until the end. Any public improvisation requires us to continue regardless of how far we might stray from our intended path. Choosing a word for the year is a way to maintain our focus. We might wander into some foreign keys, use a few chords from outside our tonal language, but if we can reclaim our focus, we should be able to bring our improvisation to a successful conclusion.

Counterpoint

My word and area of focus in improvisation for 2016 is counterpoint. My goal for 2016 is to be able to comfortably improvise a fugue in four parts on a hymn or chant. There was a time when I felt competent to at least try a fugal exposition, but after many years of neglect, whatever of those skills I had has fallen out of practice. As the saying goes, “If you don’t use it, you lose it.” Such has been my contrapuntal improvisational skills, and my aim in 2016 is to remedy that.

As we journey through 2016, I intend to share my progress and the resources I discover and use here so that 1)I am publicly accountable for my focus and goal, 2)other readers and organists may benefit from my discoveries, and 3) others may offer their own feedback and suggestions to help my progress. Please feel free to drop me an email or comment if you have suggestions or resources that you have found particularly helpful in your own study of counterpoint.

Textbooks

To get us all started, here are the books on counterpoint in my library that I intend to review this week as I sort out the best way to improve my skills:

- Johann Joseph Fux: Study of Counterpoint (Gradus Ad Parnassum)

- Knud Jeppesen: Counterpoint

- Harold Owen: Modal and Tonal Counterpoint

- Kent Kennan: Counterpoint (I have the 3rd Edition)

- Thomas Benjamin: Counterpoint in the Style of J.S. Bach

Each of the above links are to Amazon.com. Any purchases made through the links will go towards the support of this website. As I was looking for the books on Amazon, I noticed a few other books on counterpoint that looked interesting, but since these five are already in my library, I thought they would be the best place to start. I’d love to hear about your experiences with these or any other books on counterpoint for this journey through 2016.

My word for improvisation is counterpoint. What is yours?

Wishing you all the best for 2016!

Glenn

Newsletter Issue 54 – 2016 01 04

See the complete list of past newsletter issues here.

Sign up to receive future issues using the box to the right on this page.

Sacred Time

One of my central beliefs is that improvisation is a skill that can be learned through practice. If you have learned to read and write in any language and have learned to play the organ, then you should be able to learn to improvise. Some gift or talent may be required to get to the level of Gerre Hancock or Pierre Cochereau, just as we are all capable of carrying on an improvised conversation with another person, we should be able to learn the basics of improvising music.

Language Practice

Conversation is a skill that we practiced every day as a child. Our parents, family, and friends corrected us and helped us to pronounce words correctly and form sentences with proper grammar. We were coached every day for many years in order to develop these skills. We heard these skills practiced by others for hours every day, and practiced for ourselves almost as much. After a few years of informal tutoring, we were sent for formal schooling in spelling, grammar, and eventually studied larger structures such as form, plot, and character development.

Music Practice

Contrast this approach to how we learn music. We may hear it everyday, but how many of us practice making music every day? Let alone, how many of us have practiced music every day for years? How many times did your parents have to tell you to practice your music? I know I certainly went through phases when I wasn’t interested in practicing, and even when I wanted to practice, if I could get to the organ three days a week that was a good week!

Think also for a moment about the difference in method of learning music. Depending upon your country and what sort of music first caught your attention, there’s a strong chance that you actually had to learn to read music before you ever got to make music. When speaking a language, it is the reverse: we learn to speak and converse before we ever learn to read and write. Much of our music instruction is focused on learning to read and write rather than on speaking and creating. No wonder we have so much difficulty with and fear of improvising!

Sacred Practice

Whether music is your full-time job or only a part-time concern, because practice may have only been a daily habit when (if) it was required for school, it often gets pushed down towards the bottom of our to-do lists. It is very easy to let other tasks, especially administrative ones, take up most of our time.

I attended a very demanding academic high school and my musical studies were always in addition to my schoolwork. When I began my undergraduate studies with music as my primary focus, even though I had a full course load of 18 credits, I was not as challenged, so the next semester I took an overload of 22 credits — all one and two credit music classes. That semester, my organ teacher told me that I needed to make my practice time sacred. With so much on my calendar, it would have been very easy to let my practice time get bumped for other activities and rehearsals. Making my practice time sacred meant that nothing else could reschedule it. There were only limited number of hours on the instrument where I had my lesson, so whenever I signed up to practice there, those hours became sacred. No other homework or rehearsals could usurp those organ practice hours.

Application

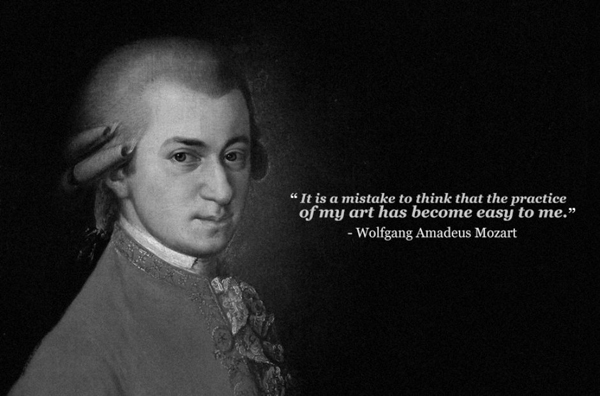

At one point, the column on improvisation in The American Organist was titled “Learn to improvise in 15 minutes a day.” Improvisation is a skill that we can learn through practice, but, like any language, it takes daily practice. Musical practice time is not built into our day like conversation practice, so I suggest we find a time to make sacred for our music. Perhaps it is only ten minutes a day. Maybe it is three different hours in a week. I would love to have again the two hours a day that I eventually reserved for practice as an undergraduate. Whatever time you choose, be intentional about your selection, and make the time sacred. After all, even Mozart practiced….

Happy practicing!

Glenn

Newsletter Issue 53 – 2015 12 07

See the complete list of past newsletter issues here.

Sign up to receive future issues using the box to the right on this page.

Modeling Tournemire: Offertoire

As I prepare to play selections from Tournemire’s L’Orgue mystique for All Saints this weekend, I thought we’d look at the second movement for some improvisation ideas.

Form and Language

The Offertoire for All Saints is based on the chant Justorum animae. The short piece contains five sections: A)harmonized chorale, B) monophonic chant, A’)elaborate harmonized chorale, B’) shorter monophonic chant, C) Coda.

The chant is in Dorian, Mode 1, so though there are no alterations in the key signature, because Tournemire starts the chant on G, every B is flatted except at the final cadences of the A sections. He borrows from closely related modes by including E-flats and A-flats. The chant is presented in half notes in the soprano, but Tournemire suppresses all the repeated notes, making each pitch of the chant equal in duration. While a traditional Bach-style chorale harmonization would include many root position chords, Tournemire rarely uses root position triads. Sevenths, suspensions, and inversions keep the progression unstable even at the cadence in the middle of the section at the end of the first phrase of the chant. The voices move mostly with step-wise motion.

The second section is a monophonic statement of the last two phrases of the chant. The change of registration and texture provide a contrast to the opening chorale. The relative speed of the chant also changes dramatically from half-notes to eighth-notes.

The return to the opening material for the third section is on a slightly softer registration and now includes more motion. While there were occasional eighth-notes in the first harmonization, this repetition keeps to the same harmonies, but includes constant eighth-note motion.

The fourth section is an echo of the second. The registration is softer, and only the second (final) phrase of the chant is cited. The final section seems to be a return to the opening material, but does not cite any of the chant. It is more of an extended harmonic return to an open fifth on the tonic G.

As offertories often take different lengths of time in different places, it strikes me that this piece could be easily shortened if needed by leaving out a section (or two or three). It would also be possible to repeat the longer B section instead of the shorter B’ section in order to lengthen the piece. While I do not know that Tournemire intended a performer to do these things, if we consider these pieces as examples of how we can improvise and fulfill the musical needs of the liturgy, I see no reason not to alter the number of sections we might play.

Applications

To summarize, here are ten ways to apply ideas from Tournemire’s Offertoire in our improvisations:

- Alternate contrasting sections to create a piece to cover an unknown length of time.

- Borrow from closely related modes or keys for harmonic interest.

- Use inversions and suspension to keep the piece moving forward.

- Suppress repeated notes in the melody.

- Standardize the rhythm of the melody into one time value.

- Change the unit of standardization for contrasting formal sections.

- Use single voice textures.

- Plan for repetition. Make sure you can play what you just played again.

- Repeat with variation. Keep it the same, but add more motion.

- Use registration to help mark formal sections.

As an example, I recorded an improvisation on Veni Veni Emmanuel following the model of this movement which you can watch here. As I recorded it before writing this column, I’m not sure I followed all ten of the above ideas, but hopefully it demonstrates at least some of the ways to apply ideas from Tournemire to a new theme.

Happy Halloween!

Glenn

Newsletter Issue 52 – 2015 10 31

See the complete list of past newsletter issues here.

Sign up to receive future issues using the box to the right on this page.

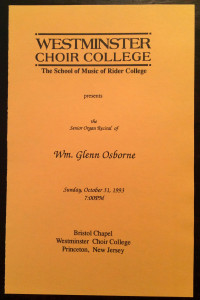

Modeling Tournemire: Preludes

I planned my senior recital at Westminster Choir College for Sunday evening, October 31, so I decided to include some selections appropriate for the day. I opened with the Bach Toccata and Fugue in D minor, concluded with the Toccata from Louis Vierne’s Pièces de Fantasie. In the middle of the program, I played the complete L’Orgue mystique, no. 48 for All Saint’s (November 1). this was the second suite from L’Orgue mystique that I learned. The first was no. 17 for Easter which I had learned and played for a chapel service earlier in the spring at the request of my chant teacher, Fr. Gerard Farrell. Fr. Farrell was not only a chant scholar, he was an organist and had studied with Flor Peeters. Fr. Farrell’s love of chant the organ music based on it definitely led to my interest in the music of Tournemire and improvisation.

I planned my senior recital at Westminster Choir College for Sunday evening, October 31, so I decided to include some selections appropriate for the day. I opened with the Bach Toccata and Fugue in D minor, concluded with the Toccata from Louis Vierne’s Pièces de Fantasie. In the middle of the program, I played the complete L’Orgue mystique, no. 48 for All Saint’s (November 1). this was the second suite from L’Orgue mystique that I learned. The first was no. 17 for Easter which I had learned and played for a chapel service earlier in the spring at the request of my chant teacher, Fr. Gerard Farrell. Fr. Farrell was not only a chant scholar, he was an organist and had studied with Flor Peeters. Fr. Farrell’s love of chant the organ music based on it definitely led to my interest in the music of Tournemire and improvisation.

The Prélude

The first movement of the suite for All Saints is a simple one page prelude. It alternates a brief harmonic progression with accompanied presentation of portions of the introit chant Gaudeamus omnes in Domino. I have marked up a copy of the score here showing the alternating sections. In it’s simplest description, the piece is a seven part rondo: ABABABA with A being simple harmonic fill and B containing the theme. This plan of alternating sections will be our model for the form. The tonal language of the accompaniment is simple, staying virtually all the time in the mode of the chant providing atmosphere more than following traditional harmonic progressions.

Advent

In Tournemire’s day, the organ was not used during the season of Advent except on the third Sunday, referred to as Gaudete Sunday and the Feast of the Immaculate Conception. As most organists continue to play during the Advent season now, I thought it would be a good idea to take themes from Advent and apply Tournemire’s forms and ideas to them in order to fill in the gap in today’s repertoire not covered by L’Orgue mystique. Perhaps the best know Advent theme today is Veni Emmanuel, a modal chant tune that I’m sure Tournemire would have used if he had needed to write more organ music for the season.

One of the tasks that I’ve suggested from time to time that will help us become better improvisations is to actually take pencil and paper and write out our ideas. I took the time to craft a Prélude à l’Introït on Veni Emmanuel following rather closely Tournemire’s prelude for All Saints. (Donwload the score here.) While I can claim it as a composition, it really is simply an example of how we can take the form and ideas from Charles Tournemire and apply them to themes that we know and use in our liturgies today. I encourage you to play through both the scores and to try your hand at improvising your own prelude following this model on a theme of your choice.

Videos

While I haven’t managed to make a video lesson of this yet, I was able to record performances of both the All Saints Introit and my Advent version. I also recorded an improvisation on Adoro Te Devote following the same idea (and registration). None of these is terribly long, but they can be fabulous ways to fill a couple of minutes, introduce a new tune to the congregation, or even provide an introduction to singing a hymn. I hope these lessons and examples will lead you to enjoy and discover the music of Charles Tournemire as I was led to it by Fr. Farrell.

May your improvisations be inspired,

Glenn

Newsletter Issue 51 – 2015 10 04

See the complete list of past newsletter issues here.

Sign up to receive future issues using the box to the right on this page.