Over the years, I’ve been fortunate to study with many different improvisation teachers. The encounters have been in short masterclass lessons, intensive workshop immersions, and regular weekly lessons. Only once, however, has a teacher ever made an attempt to asses my improvisation skill level.

I met Franck Vaudray when I was in Lyon to audition at the conservatory (CNSM). I was in town on Sunday morning, so made a visit to St. François de Sales. I sat in a pew for mass and went up to the organ afterwards, expecting to find Louis Robilliard and planning to ask what pieces he had played. Instead, that’s when I met my next improvisation teacher.

Franck Vaudray

As I arrived at the organ while he was still playing the sortie, I instantly discovered that I was hearing an improvisation. No score by César Franck was on the music rack. (I had dismissed Charles-Marie Widor as an option once the canon appeared.) After we exchanged introductions, I learned that he also had improvised the lovely baroque trio sonata movement at the offertory. These improvisations were both so polished that they could have been written pieces, so when he offered to take me as a student, I was more than happy to begin commuting to Lyon for lessons whenever I could.

The Evaluation

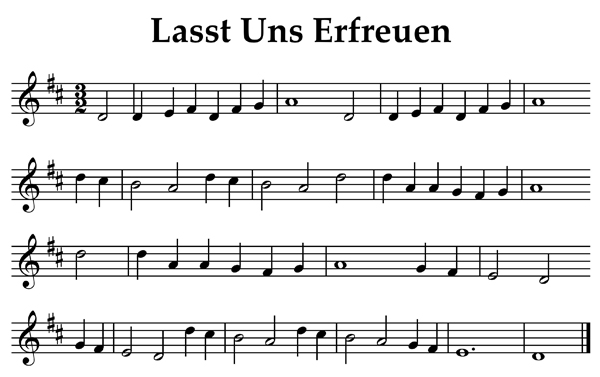

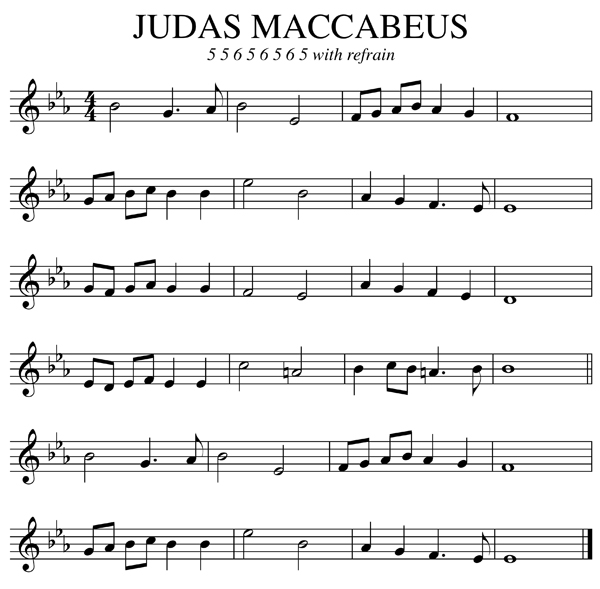

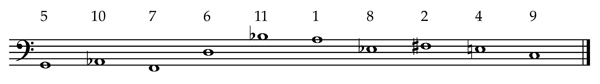

When I came back to St. Fraçois de Sales a few weeks later for my first lesson with Franck, he started by placing a piece of paper on the music rack with something like the following written on it:

(I had the original paper for many years, but it seems to have gotten lost in my last move.)

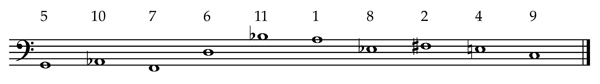

My instructions were to play single notes as fast as I could with my hands in an atonal style and then add in the theme in long notes with the pedals. While the instructions may seem simple, it can be very easy to fall into tonal patterns if you are not careful with the hands. Likewise, this duo may not seem very impressive, but with all the foundations and swell reeds coupled together, it could be the start of a very nice toccata!

Increasing Difficulty

So ends the easy part. Every step thereafter basically served to make the task more difficult. It’s hard for me to remember the exact sequence of steps, but here’s a few basic ideas of what I went through:

- Increase to trio texture. Both hands play independent atonal lines of fast notes. No rests allowed. Pedal plays them in long notes.

- Duo: Right hand and pedal alone, but this time, play the theme in retrograde (C, E, F#, Eb…)

- Duo (left hand and pedal) with the theme played from the outside in (G, C, Ab, E, F, F#…)

- Duo (both hands and pedal) with the theme from the inside out (A, Bb, Eb, D, F#, F…)

- Duo with the theme inverted (octave transposition permitted so as to not run out of notes) so it becomes: G, F#, A, C, E, F…

Is your brain tired yet? Now, it’s time to do it all over again, but this time observe the numbers as the duration of the notes of the theme. Starting again with the basic theme, this means that you would play five notes with the hands for the G in the pedal, followed by ten for Ab, seven for F, six for D, and so forth through the entire theme. I’m guessing this will slow you down a little, because it certainly decreased my speed! Be sure you go through all the retrograde, in-out, out-in, and inversion steps following the numbers as well.

Texture Inversion

For the final task, I could disregard the numbers (Yeah!) and was told to start again with long notes in the pedal and fast notes in the hands. Instead of ending after playing once through the theme, however, I was to continue playing more notes of shorter and shorter duration with the feet while the hands were to play longer and longer notes until eventually I managed to reverse the texture and could play the theme in long notes (in octaves) with the hands while the feet played the quick atonal notes. Here was the final speed test: how fast could my feet move?

To Be Continued

So that you can try this easily yourself, I created a pdf with the theme and instructions above that you can download here and print to take with you to the console. How fast can you play? Is it easy to play atonal lines with your hands? How about with your feet?

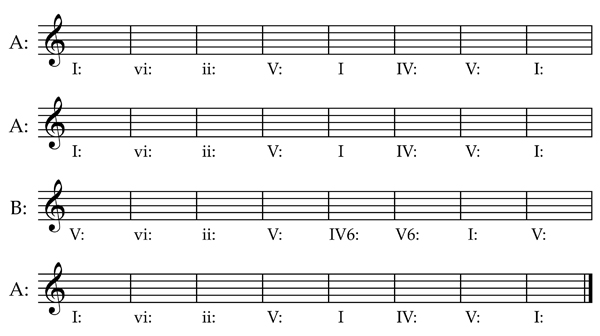

These exercises turned out to be only the first part of my first lesson with Franck Vaudray. We continued on for at least an hour more through challenges involving dictation, motives, transposition, canons and harmonization. (If I can find the sheet he gave me as homework, I’ll share more of these in a future newsletter.) I walked out of St. Fraçois de Sales mentally exhausted. When was the last time you tested your improvisational limits?

Hoping your improvisations set new speed records!

Glenn

Recent additions to organimprovisation.com:

Mode:

Newsletter Issue 23 – 2014 10 06

See the complete list of past newsletter issues here.

Sign up to receive future issues using the box to the right on this page.

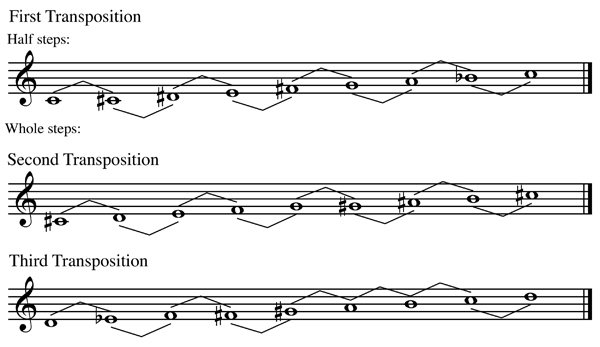

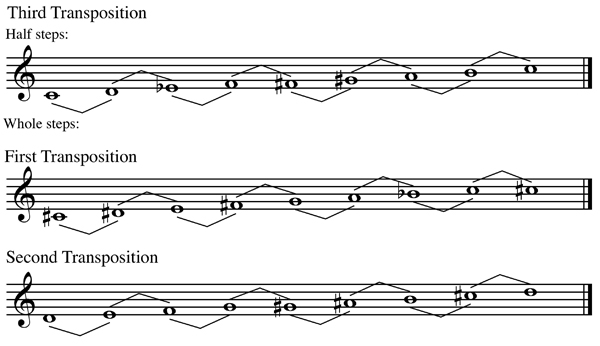

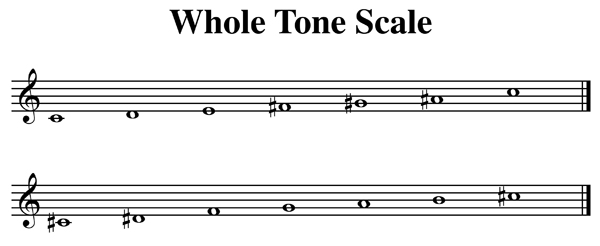

, Olivier Messiaen identifies seven modes of limited transposition. Within the chromatic system of twelve sounds, Messiaen has identified groups of pitches which after a certain number of transpositions are no longer transposable. These modes may be used both melodically and harmonically and give the impression of several tonalities without polytonality. The first of these modes is the whole tone scale. The second mode is probably the best known of the modes Messiaen identifies as it is also known as the octatonic scale.