Starting a new year often involves setting goals and renewed energy to work on projects that may have fallen by the wayside. My plan for 2019 is to send out at least two emails a month with resources or ideas to help you become a better improviser. to get us started, I want to take a look at a new resource that could provide us with a whole year of work, if not more!

Breaking Free

In 2011, Jeffrey Brillhart gave us Breaking Free. It is a very thorough and progressive resource for developing a personal musical language drawing inspiration from many of the 20th-century French masters. In my review of the book, I lamented the lack of specific tasks for the student. While useful for a teacher of improvisation, I wasn’t sure the uninitiated student would know what to do with all the wonderful material presented there. Just before Christmas, I received a new book by Jeffrey Brillhart that clearly addresses that concern.

A World of Possibilities

Subtitled “Master Lessons in Organ Improvisation,” A World of Possibilities contains 32 units. Each unit provides an exposition of material to cover and specific assignments for the student to improvise in order to master the material. Even in the first eight units where tonal language is the primary material, a form is given for the assignment. The result is that one is almost always improvising a complete piece that might be performed in front of an audience or used in worship!

Composition Models

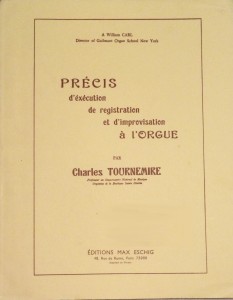

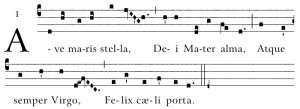

In Breaking Free, form is reserved for the last few chapters

and discussed very broadly. In this new book, he gives us concrete

analysis of two major works for organ: Charles Tournemire’s L’orgue Mystique, Opus 55, no. 7 (Epiphania Domini) and Maurice Duruflé’s Prélude, adagio et chorale varié sur le theme du ‘Veni Creator,’ op.4.

The Tournemire takes two units and the Duruflé three units. Brillhart

breaks down the structure of each of the pieces and identifies elements

for students to include in their own improvisations.

Sandwiched between Tournemire and Duruflé are five units on the language

of Messiaen. Other middle units cover versets, the acoustic scale,

shifting modes, improvising on emotional states, visual images, text and

variations. After the Duruflé units are four on symphony and a final

one on silent film accompanying.

Teaching improvisation

Organists seem to be a rare breed these days. Those who improvise in

public are even rarer. Those who understand improvisation well enough to

teach it well seem to be the rarest of the rare. Jeffrey Brillhart

demonstrates with A World of Possibilities that he is indeed a

master teacher of improvisation. The book deserves its subtitle: “Master

Lessons in Organ Improvisation.” No matter what skill level the student

begins with, each assignment provides a challenge, and no matter how

hard the challenge may seem, it seems only a short distance away from

the previous assignment.

The material is dense, and you will need a copy of Breaking Free in order to take full advantage of A World of Possibilities.

A simple assignment instruction, perhaps only one sentence, might take a

week of practice to explore and master. The organization and structure

of the book however make sure that if you spend the time, you will

become a better improviser and be prepared to tackle the next

assignment.

If you are looking for a way to track your progress and improvise better

in 2019, I can think of no better way than to pick up the two books by

Jeffrey Brillhart and get to work.

Happy improvising,

Glenn Osborne

![vierne[1]](http://www.organimprovisation.com/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/vierne1-300x194.jpg)