One of my central beliefs is that improvisation is a skill that can be learned through practice. If you have learned to read and write in any language and have learned to play the organ, then you should be able to learn to improvise. Some gift or talent may be required to get to the level of Gerre Hancock or Pierre Cochereau, just as we are all capable of carrying on an improvised conversation with another person, we should be able to learn the basics of improvising music.

Language Practice

Conversation is a skill that we practiced every day as a child. Our parents, family, and friends corrected us and helped us to pronounce words correctly and form sentences with proper grammar. We were coached every day for many years in order to develop these skills. We heard these skills practiced by others for hours every day, and practiced for ourselves almost as much. After a few years of informal tutoring, we were sent for formal schooling in spelling, grammar, and eventually studied larger structures such as form, plot, and character development.

Music Practice

Contrast this approach to how we learn music. We may hear it everyday, but how many of us practice making music every day? Let alone, how many of us have practiced music every day for years? How many times did your parents have to tell you to practice your music? I know I certainly went through phases when I wasn’t interested in practicing, and even when I wanted to practice, if I could get to the organ three days a week that was a good week!

Think also for a moment about the difference in method of learning music. Depending upon your country and what sort of music first caught your attention, there’s a strong chance that you actually had to learn to read music before you ever got to make music. When speaking a language, it is the reverse: we learn to speak and converse before we ever learn to read and write. Much of our music instruction is focused on learning to read and write rather than on speaking and creating. No wonder we have so much difficulty with and fear of improvising!

Sacred Practice

Whether music is your full-time job or only a part-time concern, because practice may have only been a daily habit when (if) it was required for school, it often gets pushed down towards the bottom of our to-do lists. It is very easy to let other tasks, especially administrative ones, take up most of our time.

I attended a very demanding academic high school and my musical studies were always in addition to my schoolwork. When I began my undergraduate studies with music as my primary focus, even though I had a full course load of 18 credits, I was not as challenged, so the next semester I took an overload of 22 credits — all one and two credit music classes. That semester, my organ teacher told me that I needed to make my practice time sacred. With so much on my calendar, it would have been very easy to let my practice time get bumped for other activities and rehearsals. Making my practice time sacred meant that nothing else could reschedule it. There were only limited number of hours on the instrument where I had my lesson, so whenever I signed up to practice there, those hours became sacred. No other homework or rehearsals could usurp those organ practice hours.

Application

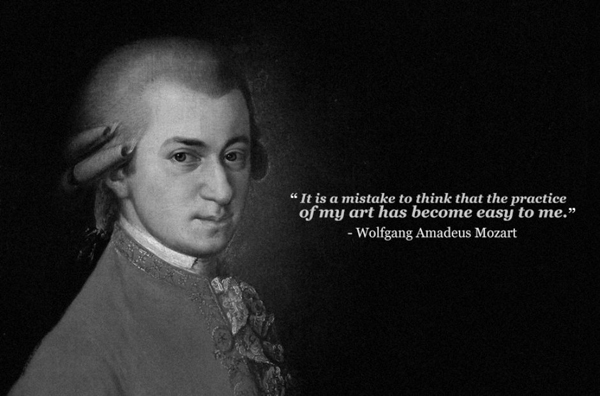

At one point, the column on improvisation in The American Organist was titled “Learn to improvise in 15 minutes a day.” Improvisation is a skill that we can learn through practice, but, like any language, it takes daily practice. Musical practice time is not built into our day like conversation practice, so I suggest we find a time to make sacred for our music. Perhaps it is only ten minutes a day. Maybe it is three different hours in a week. I would love to have again the two hours a day that I eventually reserved for practice as an undergraduate. Whatever time you choose, be intentional about your selection, and make the time sacred. After all, even Mozart practiced….

Happy practicing!

Glenn

Newsletter Issue 53 – 2015 12 07

See the complete list of past newsletter issues here.

Sign up to receive future issues using the box to the right on this page.