I am always doing that which I cannot do, in order that I may learn how to do it.

― Pablo Picasso

Last week we looked at the Dorian Mode. In addition to proposing some exercises to help you practice it, I mentioned how we each have a preferred sensory method for learning, either visual (seeing), auditory (hearing), or kinetic (touching). As musicians, there would seem to be a bias towards learning through listening, however I know I am a strong visual learner: if I try to play a piece I know from a different edition of the score, it feels like I’m learning it all over again! I’ve always known that one of the greatest hurdles to improvising is the the fear of not having a score on the music stand, but perhaps that’s related to a person’s learning mode more than not knowing what to play? Which mode do you favor when learning music? Is it different from how you might learn other subjects?

Global or Detail

Are you a big picture person? How closely do you pay attention to details? If you are giving directions on how to get somewhere for someone, how much detail do you provide: general guidance (left at the end of the street, then left at the third light) or turn by turn instructions with descriptive landmarks (left when the road ends at the airport, through three lights, crossing route 50, turning left on Maguire after passing the mall before entering the next subdivision)?

I recognize that my first approach to an area is from the big picture perspective. You can call this “Ready, Fire, Aim.” (There’s even a book by this title: Ready, Fire, Aim: Zero to $100 Million in No Time Flat about building a business this way!) Want to learn to improvise? Start by sitting down at the bench and playing. Next step, refine what you played into something better. This is how to get over that first hurdle of playing without a score in front of you. The big picture viewpoint to to simply start playing something. Afterwards, we aim for improvement and choose a direction to focus our attention.

The detail oriented perspective requires more preparation. For example:

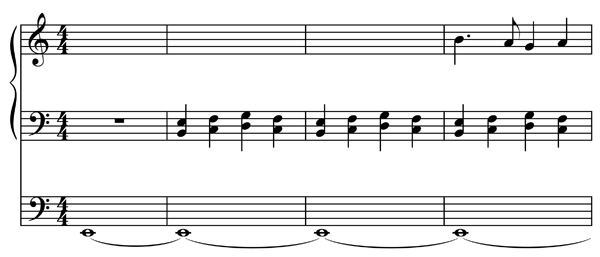

- Choose a mode to learn (Phrygian)

- Play the tonic of the mode in the lowest octave of the pedal on soft 16′ & 8′ stops

- Play a quarter note ostinato pattern with the left hand on soft 8′ foundations – perfect fourths with the top note melody being E-F-G-F.

- Finally add a melody on a solo stop played by the right hand.

- Begin the melody on something other than tonic. Create a four measure phrase before arriving at tonic.

- Create a second four measure phrase that contrasts with the first phrase.

- Conclude by repeating the first phrase.

See the example below for a sample start following the detailed instructions above:

In some ways, the detailed approach can provide more success, but it also leaves less room for creativity. What happens when we play a note outside the mode with our right hand? Do we stop? Is that instantly a bad improvisation? Do we brand ourselves a failure and never improvise again? Of course not! Sometimes a little slip can focus our attention and help us move into flow making an even better overall performance!

Teaching and Learning

The best teachers are able to meet the student where he or she is and open doorways to new areas of learning, providing the right amount of detail to enable the student to step through those doorways. In the end though, it is up to the student to step through the doorway. Are you practicing your improvisation skills? Are the instructions I am providing detailed enough for you or are they too general? What else can I do to help you become a better improviser? If these posts are helpful, please sign-up for the newsletter or take a moment to let me know more about you and your interests in improvisation by leaving a comment below. The more I know about you, the more useful this newsletter and website will become.

Whether working from generic or detailed plans, hoping all your improvisations are masterful,

Glenn

Recent additions to organimprovisation.com:

Organists:

Mode:

Themes

Newsletter Issue 19 – 2014 09 08

See the complete list of past newsletter issues here.

Sign up to receive future issues using the box to the right on this page.