Here in the northern hemisphere, it’s summer. Even after moving further north from Orlando to Baltimore, we still have frequent afternoon thunderstorms. All this rain reminded me of two more ways we can work with the ideas from last week.

Review

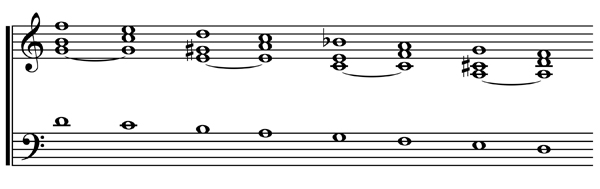

Here’s the progression from Maurice Clerc again:

Registration

Did you practice this progression (or something similar) this week? The first registration suggestion was to use celestes to accompany a flute solo. The second option was for a solo in the tenor range. If you tried the tenor solo, did you use your right or left hand for the solo? Hopefully you made some progress toward mastering these registrations and are now ready to add a new texture to the improvisation!

Raindrops

Keep the celestes as the accompaniment, but now add something sparkly to the flute solo, like a larigot or sifflote. Instead of playing long connected legato lines, your task is to make raindrops – super short staccato notes – on this sparkly registration. Because rain falls pretty quickly during a nice summer shower, be sure to spend some time practicing just the rain with the chords to make sure you can think faster than your fingers play! I prepared a handout to demonstrate each of the three dispositions.

Advanced options

If you happen to have an organ with a pedal divide, you can actually put the melody in the pedal (right foot) while still playing a bass part with the left. And lest you feel unchallenged because you don’t have a pedal divide, try thumbing the melody on another keyboard while still playing the raindrops and accompanying chords. From top to bottom, registrations on the keyboards would be: Top=celestes, Middle=Solo, Bottom=Raindrops. If you can master this disposition, people who aren’t able to see what you are doing will think you’ve grown another arm!

Another free method

After sharing First Lessons in Extemporizing on the Organ by Hamilton Crawford Macdougall, several readers pointed me to resources where I’ve been able to locate other method books available for download. This week I spent looking at Organ Accompaniment and Extempore Playing by George E. Whiting. It is available through IMSLP which is a fabulous source of scores if you are not already aware of it.

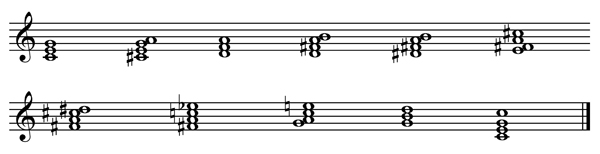

The book claims to be the only work that treats choir accompaniment and improvisation together. Given that it was first published in 1887, I suspect that was true at the time. The improvisation instruction begins with imitating hymns. These imitations become interludes, modulations, and then periods. Here’s one example of a modulation sequence which he suggests learning:

Because the book also focuses on accompaniment, one of the common themes becomes registration and how to make the organ sound at its best. While some of the ideas are opinionated:

As for the Flutes –especially the Stopped Diapasons– I consider them of the least consequence of any of the various tone qualities of the organ. They are the most cheaply built of any of the registers, and small, inferior organs are apt to be full of them.

Others are more practical:

Light passages, rapid scales, staccato chords, arpeggios, trills, etc., are not appropriate to the Diapasons of either manual: this family of stops requiring a grave, church-like style of performance, such as chorals, linked chords, contrapuntal effects, and slow arpeggios.

While the improvisation instruction is nothing that couldn’t be found in any number of newer methods, if you want to improvise in a late 19th century style, this book provides lots of key ideas about how to register the organ and, through the examples of accompaniment and orchestral transcription, what sort of disposition of voices sound best.

Summer Rain

In addition to being a season when I can expect rain outside to enable the plants to grow, I hope these emails provide nourishment for your growth in improvisation. It has been a pleasure to receive emails from several of you lately. These messages nourish me and keep me looking for ideas and ways to help you. Thank you for subscribing.

Hoping this season brings growth in your improvisation skills,

Glenn

Newsletter Issue 41 – 2015 07 01

See the complete list of past newsletter issues here.

Sign up to receive future issues using the box to the right on this page.