Thank you to everyone who has completed the survey from the last newsletter about a workshop next summer in Baltimore! So far, it looks like July is the preferred month, but you can still make your voice heard here. I’m excited by the interest demonstrated in the responses and will keep you posted as the event takes shape.

Solo Pedal

A regular part of my early organ studies was devoted to pedal practice. Whether it was exercises by Stainer, Gleason or Nilson, a significant chunk of my practice time was spent acquiring the ability to find my way around the pedal board. The end goal however was always to combine the feet with the hands. Aside from a few cadenza passages, we rarely play with out feet alone after we master the basic technical exercises.

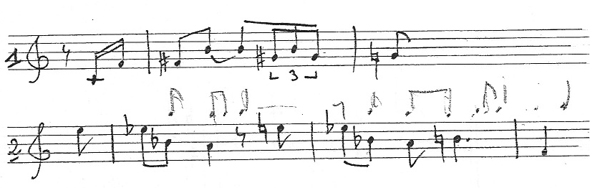

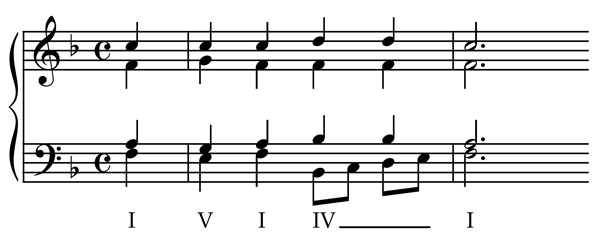

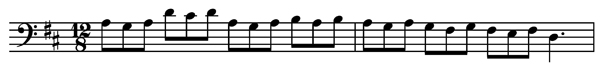

After creating the virtuoso pedal variation on Salzburg, I realized how easy it would be to progress to solo pedal variations. Where we made the virtuoso pedal part by playing the bass and ornamenting the tenor, we could play the soprano ornament the bass, perhaps something like this:

Sometimes it might be easier (or sound better) to use the alto as a harmony part rather than the bass. When there is a half note in the melody, we can choose to find some way to fill in order to keep the motion going (I added passing notes above), or we could slow the motion down to eighth notes or even have a quarter note if we need a break in our virtuosity!

Ornamented Melody

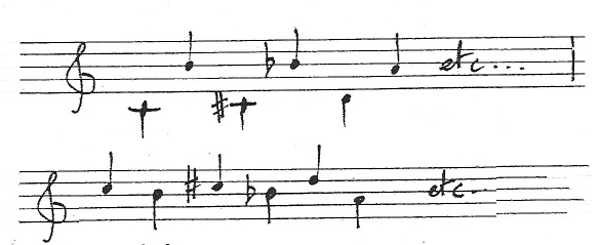

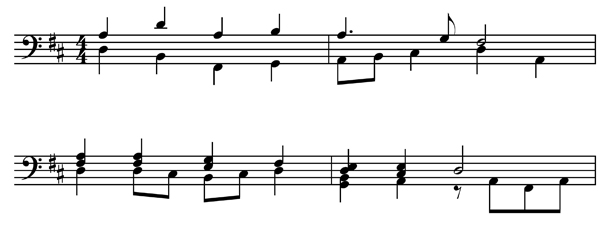

As Salzburg has several large skips in the melody, we could create another simpler variation by using choosing to only ornament the melody with neighbor tones:

And of course, one of the most impressive pedal techniques is to play notes with both feet at the same time, adding in three- or four-note chords for the biggest splash:

While these solo pedal variation techniques might better be suited to concert use than liturgical use, they are still useful tools for our improvisational toolbox. If we need to practice our pedal technique, we might as well practice our improvisation skills at the same time. Besides, wouldn’t a flashy pedal cadenza be a great touch to add to the end a toccata?

Hoping your feet will soon be flying across the pedalboard,

Glenn

Newsletter Issue 38 – 2015 05 26

See the complete list of past newsletter issues here.

Sign up to receive future issues using the box to the right on this page.