No one likes to wait, and silence can be deadly.

When that unexpected silence arrives in a church service, who is asked to fill the void?

Why, it’s the organist, of course!

This might mean extending a piece for a few more measures, or it might mean creating a new piece just long enough to fill the gap (even when you don’t know how long that gap might be).

Aimless Wandering

At the most basic level, any organist should be able to fill time. Creating an additional repeat in a written piece of music or even starting again at the beginning and bringing the piece to a successful cadence when the time is up are the simplest ways to start. While I recommend aimless wandering as a way to explore new modes or when searching for your own harmonic language, when the organist just meanders meaninglessly around the keys to fill time, it becomes killing time and I think silence might actually be a better option.

Following a form

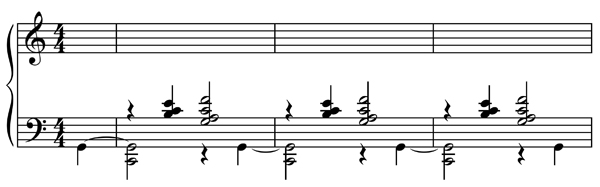

The much better option is to actually follow some sort of form in the extension that you need to create, or if you expect to have the time for an entire piece, then you definitely need to have a form in mind. I find one of the easiest and most flexible forms is AABA or song form. There are many hymn tunes that follow this form (HYMN TO JOY and NETTLETON to name only two), and unless your B section is radically different, there’s a good chance that you can end your piece at the end of any section without too much concern.

Simple Structure

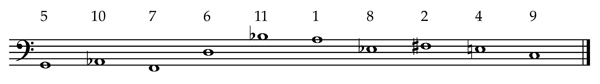

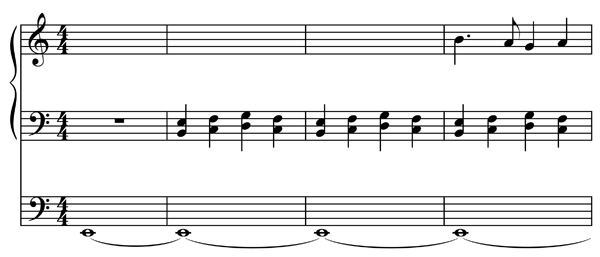

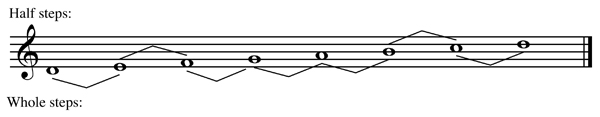

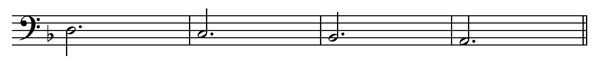

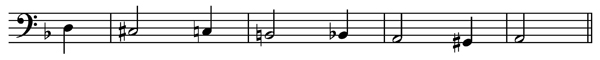

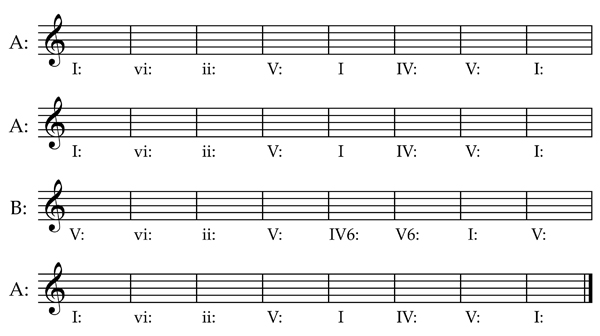

If you are in need of an extension, the easiest material to use for the A section is a phrase or idea from the piece you just played. If you need to start from scratch, here is a simple harmonic scheme that you can follow:

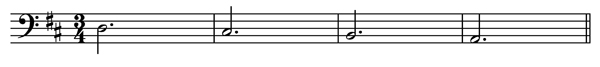

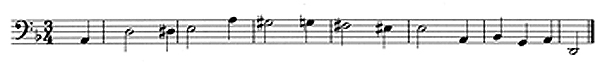

You could plan out more elaborate structures according to your ability level, and of course, this can be adapted for any key or time signature. One easy way to stretch this form would be to double the phrase length to eight measures. For example:

At a moderate tempo, either of these examples could provide you with 1-2 minutes of music. I prepared a PDF that you can download here to print both of these on one page to take to the console and practice. Feel free to create your own patterns to practice the form.

Longer Songs

Once you are comfortable creating a 16 or 32 measure song form, you can then practice stringing them together to create a larger ABA or even AABA form. If you choose to follow a larger AABA form, be sure to differentiate your two A sections by changing the accompaniment pattern or the register of the melody or perhaps even both. By doing something slightly different, you help to keep the listener involved with the piece. By using the same material again, you will be making your job as an improviser easier, so it becomes a win-win situation for everyone!

Silence can torture, but so can rambling aimlessly. If you have a gap to fill, make sure you are following a form rather than just killing time.

May all your songs be filled with beautiful melodies,

Glenn

Recent additions to organimprovisation.com:

Organists:

Theme:

Newsletter Issue 25 – 2014 10 21

See the complete list of past newsletter issues here.

Sign up to receive future issues using the box to the right on this page.