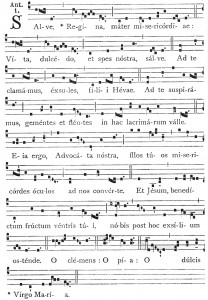

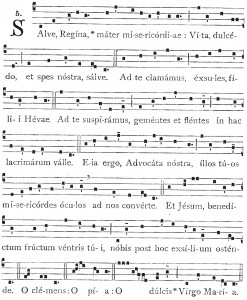

In the French Classical period, composers wrote suites of pieces that were used in alternation with the choir. The choir would sing a verse of chant and the organ would play a verse, trading with each other until the entire chant text had been proclaimed. Except for the Gloria during Mass, the organ would generally play the first movement in order to establish the mode and pitch for the choir. The first movement might also clearly cite the theme as a reminder for the choir of the melody that they were about to sing.

Modes

Gregorian chant was the primary source of liturgical music during this period and was considered to be in modes rather than our modern major and minor keys. There are eight chant modes commonly referred to as:

- Dorian (D-D)

- Hypodorian (A-A)

- Phrygian (E-E)

- Hypophrygian (B-B)

- Lydian (F-F)

- Hypolydian (C-C)

- Mixolydian (G-G)

- Hypomixolydian (D-D)

The easiest way to describe these tonalities is using the white notes of the keyboard for the ranges listed next to the names above. While this is a vast oversimplification of the use of modes in chant, it will give you a basic idea of how each mode has a different character.

These modes could be transposed to other pitch centers to make it easier for the choir to sing the chants, so while you may not need to know how to play every mode starting on any pitch, in order to improvise in the French Classical style, you definitely need to know the modes. The links above and last fall’s newsletter on learning modes are places to start if you need more of an introduction.

Registration and Style

The classic plein jeu registration is:

- G.O. (Great): Bourdon 16′, Bourdon 8′, Montre 8′, Prestant 4′, Doublette 2′, Cymbale, Fourniture

- Pos (Choir): Bourdon 8′, Prestant 4′, Doublette 2′, Fourniture, Petite Cymbale

- Péd: Trompette 8′ (if used)

- Keyboards coupled

The pedal trompette is quite a loud stop compared to the typical pedal trumpets on most American organs. Take advantage of all the videos on YouTube to listen to some of the historic instruments like Poitiers, St. Maximin, or even the restored Dom Bedos in Bordeaux if you haven’t gotten to hear these sounds live and in person.

Most often these opening movements are in cut time with two slow half note pulses per measure. The writing is often in four to six voices. If there is a chant theme, it could appear in the bass or tenor. According to Dom Bedos:

Le grand plein-jeu doit se traiter gravement et majestueusement, l’on doit y frapper de grands traits d’harmonie, entrelacés de syncope, d’accords dissonant, de suspensions et surprise d’harmonie frappantes.

The great plein-jeu must be treated gravely and majestically. There one must make broad strokes of harmony, entertwined with syncopations, dissonant chords, suspensions, and striking harmonic surprises.

One of my favorite harmonic progressions from this period is where the bass makes a deceptive resolution from V to vi while the other voices resolve to a major tonic chord. For example, in A minor:

Especially in the earlier not so equal temperaments, this is definitely a striking chord progression!

Form

Unless there is a theme present, many times these pieces simply seem to wander through chains of interesting harmonies in the tonic or closely related modes. Themes tend to be in half notes in the pedal, usually in the tenor, but occasionally in the bass. Looking at a standard harmonized hymn and placing the melody in the tenor played by your feet requires practice. While not my best improvisation ever, I did manage to record a short plein jeu on Tallis’ Canon this week as a demonstration of the style and so you could hear the organ at the Cathedral. Feel free to share your own improvised plein jeu performances in the comments for this post.

Happy improvising!

Glenn

Newsletter Issue 43 – 2015 07 28

See the complete list of past newsletter issues here.

Sign up to receive future issues using the box to the right on this page.