One of the things I really enjoyed during my time in France was the study of harmony and counterpoint. My plan was to spend a year abroad in between my Master’s and Doctoral degrees here in the US. I loved living in France so much, that I eventually stayed for four years. Even though I had earned an advanced degree here, when I began study of harmony and counterpoint in France, I was placed in the class of first year students!

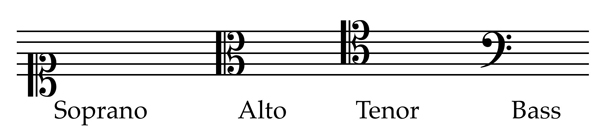

Initially, I felt a little humiliated at having to start from scratch, but I also realized that there were some skills I could acquire and improve by starting at the beginning. All exercises were written in C or F clefs (no Treble G clef). While I had learned to read these clefs in school, I figured it wouldn’t hurt to become even more familiar with them.

One of the other distinctions was that exercises were always done with pencil and paper at a desk. No keyboard (or other instrument) allowed. This forces you to hear inside your head and know what the little dots on the page actually sound like before you play them. It is possible to write lines that look great on the page and may even follow all the rules but actually sound very bad. In all my studies in the US, I do not believe we were ever denied the opportunity to check our work on a keyboard before turning it in. Believe it or not, work with pencil and paper can actually be ear training work!

From Two to Three

Have you tried to improvise any duos yet? How successful were you in creating two independent voices? My entire first year of counterpoint in France was spent writing in two voices. To truly master these contrapuntal styles takes lots of practice.

The great joy of improvising a suite is that no movement needs to be very long. Use any opportunity you have to improvise in the two part texture, even if it is only for a 15-30 second interlude or coda where you need to cover some liturgical action with music. Even if the registration is not from the French Classical period, practicing in two voices will help you become more familiar with the texture and gain fluidity. While you may not want or need to spend a year on two-part texture as I did in France, the more comfortable you are with two voices, the easier it will be to move into three parts.

Trio à Deux Dessus

There are two types of trios in the French Classical suite. The simplest to begin is the Trio à deux dessus (with two upper voices). As with the Duo, in this Trio form, the voices are generally imitative and enter one after the other, most typically from high to low. The top two voices are played with the right hand and the lower voice with the left. As with the Duos, these pieces tend to be in a triple meter, though usually with a slower implied tempo than the Duos. (Perhaps this was so the improvising organist could take a little more time to think when managing the three voices!) This doesn’t mean that they were slow, just not as fast.

Registration

The most common registration suggestion for the Trio is:

- RH (Pos): Cromorne

- LH (G.O.): Tierce, Nazard, Quarte de Nazard (2′), Bourdon 8′, Prestant 4′

Other options include:

- RH (Pos): Tierce, Nazard, Bourdon 8′, Prestant 4′

- LH (G.O.): Trompette

- RH (Pos): Tierce, Nazard, Bourdon 8′, Prestant 4′

- LH (G.O.): Clairon, Bourdon 8′, Bourdon 16′ Prestant 4′

- RH (Pos): Tierce, Nazard, Bourdon 8′, Prestant 4′

- LH (G.O.): Tierce, Nazard, Quarte de Nazard (2′), Bourdon 8′, Bourdon 16′ Prestant 4′

One of the more interesting registration suggestions by Gigault is to use the Tierce of the Grand Orgue for the upper and lower voices while playing the middle voice with the thumb on the Cromorne of the Positif! This would definitely require practice and is not necessarily well-suited to all trio textures.

Trio à trois claviers

The other Trio voicing has each voice on a different keyboard. While there are a certain number of pieces written that require three hands to play, I’m not sure these are within the realm of an improviser. Even though I have done some joint improvisation, asking someone to improvise a third voice in a strict contrapuntal style would require some real practice and perhaps some other agreements about form and structure in order to have any chance of success.

The great thing about being an organist is the ability to use our feet to play a (pedal) keyboard. French pedalboards of the time were primitive by today’s standards, so the bass voice of these trios is likely to be slower moving than the other voices. Grigny pushes the technique of the organist by providing several measures of eighth-notes in one of his hymn suites.

In general the registration for these trios with pedal looks very much like the registrations above but with an 8′ Flute in the pedal. On organs where there was a pedal coupler, it was also possible to use the Jeu de Tierce from the Grand Orgue in the Pedal.

Advice

Unfortunately, I don’t have a lot of guidance to give you for the best way to improvise a trio. Trios are the sorts of pieces where written contrapuntal studies become extremely useful. Choosing a short motif and making sure to pass it frequently from one voice to another would be a good mental focus when improvising a trio. It could also be helpful to practice improvising two voices alone with the right hand. Study the repertoire. Write out your best ideas and turn them into sequences and transpose them into other keys or modes. Above all else, practice slowly so that you have time to think (and hear) before you play.

While I believe it is easier to begin with a Trio à deux dessus, you may have an easier time with a Trio à trois claviers. Is it more complicated to add in an extra voice (with the hand) or an extra body part (the feet)? I’d love to hear which of the two is easier for you.

Hoping the joy of improvising increases with every voice you add,

Glenn

Newsletter Issue 45 – 2015 08 11

See the complete list of past newsletter issues here.

Sign up to receive future issues using the box to the right on this page.