In the French Classical suite, after the opening Plein jeu which primarily explores interesting harmonies, the second movements are often more contrapuntal in nature. Rather than jump into a Fugue, we’ll stick with the simpler Duo. Out of 55 Magnificat settings surveyed by Jean Saint-Arroman, 41 have a duo as the second verse.

Registration

The registration for the Duo varies quite dramatically by the end of the French Classical period. Early registration suggestions include:

- RH (Pos): Tierce, Nazard, Bourdon 8′, Prestant 4′

- LH (G.O.): Tierce, Nazard, Quarte de Nazard (2′), Bourdon 8′, Bourdon 16′ Prestant 4′

or

- RH (Pos): Tierce, Nazard, Quarte de Nazard (2′), Bourdon 8′, Prestant 4′

- LH (G.O.): Trompette with a foundation stop

By the end of the 18th century, other reed stops (Hautbois, Basson, Cromorne, Voix humaine) begin to show up as options for both voices. In a modification of the first option, Dom Bedos even offers the choice to use the 32′ stop for the left hand along with the tierces and nazards!

Tempo

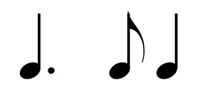

Most Duos are in the form of a gigue, so tend to be faster, lively pieces in triple meter. The following rhythm is very common:

In order to keep the piece light and active, some composers even double dotted the quarter note.

While most Duos tend to be fast, there are a few, generally in a duple meter, that would be in a more moderated tempo. Somehow, I can’t imagine playing quick double dotted rhythms with the 32′ stop Dom Bedos recommends, so the registration of the piece should also reflect the style and tempo.

Creating a Duo

As hinted above, Duos have a more contrapuntal nature. The left hand generally enters after the right hand in some sort of imitative gesture. Parallel thirds and sixths are very common, and hemiolas often appear at cadences. Any study of counterpoint usually starts with writing for two voices and would be most helpful before improvising a Duo.

The opening right hand gesture typically serves as a thematic motif for the piece and is usually about two measures long. Here are some basic steps to help you move from a motif to a full piece:

- Choose a motif with distinct rhythmic and melodic characteristics

- Practice the motif in both hands (one at a time) in multiple modes and keys

- Choose a tempo and play the motif with alternating hands in tempo (like jazz players trade solos every four bars)

- Use sequences of the motif (stepwise or circle of fifths) as you alternate hands

- Explore counterpoint for your motif. Can you play it in thirds? Sixths? What makes a good bass line for it?

- Repeat the process of alternating the motif between hands, but feel free to add in the second voice using the contrapuntal ideas you have found

- After so much exploring, it’s time to improvise a piece from start to finish. Fill in with extra material as needed. Make sure you visit one or two other key centers and bring the piece back to a satisfactory close in the tonic.

If you have not studied counterpoint, it might be helpful to plot out and notate some of your ideas. Just as an infant learns to walk while holding on to a helping hand or other object, there’s no reason not to write a few things down to serve as our support as we learn to improvise. Even writing an entire piece could be helpful.

Duos are to be lively and fun pieces, so make sure your improvisations are joyful this week!

Glenn

Newsletter Issue 44 – 2015 08 03

See the complete list of past newsletter issues here.

Sign up to receive future issues using the box to the right on this page.